Estimates vary, but these economies must collectively invest at least $1 trillion in energy infrastructure by 2030 and $3 trillion to $6 trillion across all sectors per year by 2050 to mitigate climate change by substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, a further $140 billion to $300 billion a year by 2030 is needed to adapt to the physical consequences of climate change, such as rising seas and intensifying droughts. This could sharply rise to between $520 billion and $1.75 trillion annually after 2050 depending on how effective climate mitigation measures have been.

Boosting private climate financing quickly is essential, as we detail in an analytical chapter of our latest Global Financial Stability Report. Key solutions include adequate pricing of climate risks, innovative financing instruments, broadening the investor base, expanding the involvement of multilateral development banks and development finance institutions, and strengthening climate information.

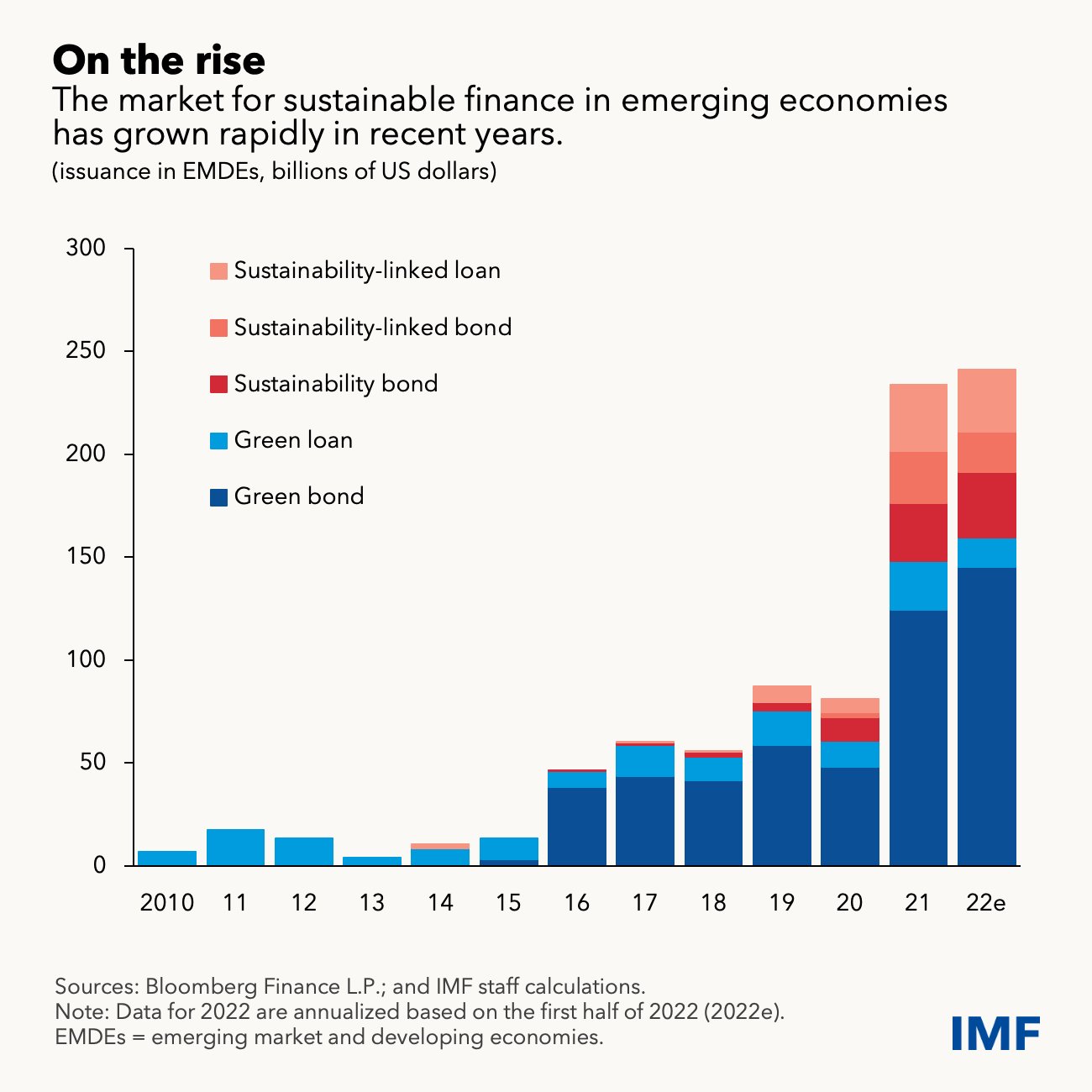

Encouragingly, private sustainable finance in emerging market and developing economies rose to a record $250 billion last year. But private finance must at least double by 2030, at a time when investable low-carbon infrastructure projects are often in short supply and funding of the fossil fuel industry has soared since the Paris Agreement.

A lack of effective carbon pricing reduces the incentive and ability of investors to channel more funds into climate-beneficial projects, as does a patchy climate information architecture with incomplete climate data, disclosure standards, taxonomies and other alignment approaches.

It’s also unclear whether very large and quickly growing environmental, social, and governance, or ESG, investment flows alone could have a real impact in scaling up private climate finance. In addition to the still-uncertain climate benefits of ESG investing, such scores for companies in emerging market and developing economies are systematically lower than those for advanced counterparts. As a result, ESG-focused investment funds allocate much less to emerging market assets. What’s more, the risks associated with investing in emerging market and developing economy assets are often deemed too high by investors.

Innovative financing instruments can help overcome some of these challenges, together with broadening the investors base to include global banks, investment funds, institutional investors such as insurance companies, impact investors, philanthropic capital, and others.

In larger emerging markets with more-functional bond markets, investment funds—such as the Amundi green bond fund backed by the World Bank’s private-sector financing arm—provide a good example of how to draw in institutional investors such as pension funds. Such funds should be replicated and expanded to incentivize issuers in emerging markets to generate a greater supply of green assets to finance low-carbon projects and attract a wide range on international investors.

For less-developed economies, multilateral development banks will play a key role in financing vital low-carbon infrastructure projects. More climate financing resources should be channeled through such institutions.

An important first step would be to increase their capital base and reconsider approaches to risk appetite via partnerships with the private sector, supported by transparent governance and management oversight.

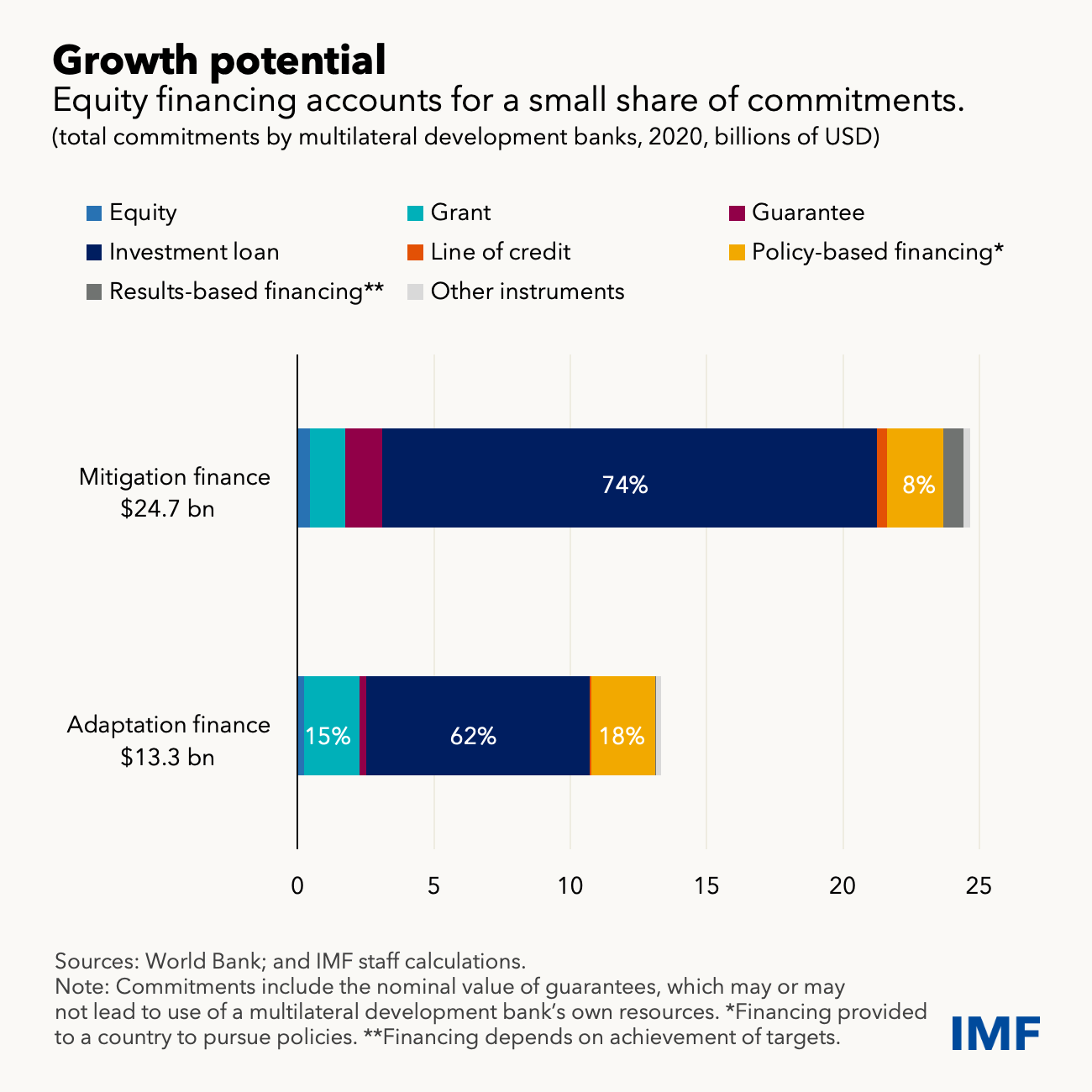

Multilateral development banks could then make greater use of equity finance—currently only about 1.8 percent of their commitments to climate finance in emerging market and developing economies. And their equity can draw in much larger amounts of private finance, which currently is equal to only about 1.2 times the resources these institutions commit themselves.

An important tool needed to help incentivize private investment is the development of transition taxonomies and other alignment approaches, which identify financial assets that can reduce emissions over time and incentivize firms to transition towards emission reduction goals.

Importantly, they include a focus on innovation in industries like cement, steel, chemicals, and heavy transport that cannot easily cut emissions because of technological and cost constraints. This helps ensure these carbon-intensive industries—those with the greatest potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions—are not sidelined by investors but rather incentivized to reduce their carbon impact over time.

The IMF is playing an increasingly important role, including through its new Resilience and Sustainability Trust which is intended to provide affordable, long-term financing to help countries build resilience to climate change and other long-term structural challenges. We have pledges totaling $40 billion and staff-level agreements on the first two programs—Barbados and Costa Rica. This trust could catalyze official and private sector investments for climate finance.

The IMF is also promoting the availability of quality climate data and fostering the adoption of disclosure standards and transition taxonomies to create an attractive investment climate.

More broadly, we are helping to strengthen the climate information architecture through the Network for Greening the Financial System and other international bodies to support emerging market and developing economies with climate policies, including carbon pricing. As the move to greater private climate financing takes hold, the Fund will engage partners and promote solutions wherever possible.

—This blog is based on Chapter 2 of the October 2022 Global Financial Stability Report, “Scaling Up Private Climate Finance in Emerging Market and Developing Economies: Challenges and Opportunities.”